Computer sabotage of the Olympic Games: the example of Olympic Destroyer in Pyeongchang in 2018

In a few months’ time, the Olympic and Paralympic Games will be held in Paris. As part of our Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) analyses, we publish a series of reports on the state of the threat targeting the major events of the year: whether sporting or political. This month, we look at the risk of computer sabotage at major sporting events.

According to the ANSSI definition, computer sabotage operations consist of ‘rendering inoperative all or part of an organisation’s information system (including industrial systems) via a cyber attack’.

The opening ceremony of the 2018 Pyeongchang Games was the scene of one of the most significant cyber attacks in the cyber history of the Olympics, named Olympic Destroyer and carried out by the Sandworm intrusion set. How did it work? What were the consequences? Who was responsible for the attack? This article sets out to answer all these questions.

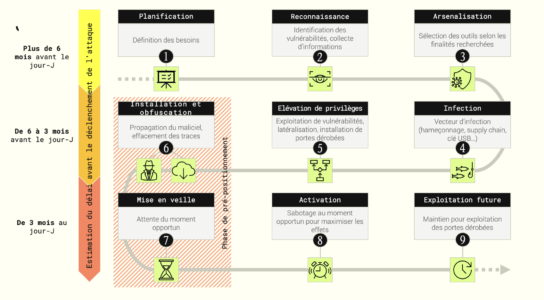

A pre-positioning attack that starts with a phishing campaign

The 9 stages of computer sabotage

The opening ceremony took place on 9 February 2018: it was at this high-profile event that the final phase of the cyber attack took place. In reality, the attack had begun a few months earlier, with the reconnaissance and infection phases carried out by Sandworm‘s operators taking place approximately between the beginning of November 2017 and February 2018. In fact, sabotage attacks require a reconnaissance time of several months, even when they are motivated by opportunism. In a pre-positioning sabotage attack, a victim is compromised several months before the payload is detonated. For attackers, it is essential to have enough time to position themselves laterally and identify the most critical assets, i.e. those whose operation they wish to disrupt.

The cyber attack began with a classic phishing campaign. It was observed that at least 5 Sandworm operators sent emails with booby-trapped links to stakeholders (providers) of the Olympic Games, impersonating certain players in the event: the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the Korean National Counter-Terrorism Centre or even the CEO of the provider company responsible for timekeeping at the Olympic Games. Finally, a company providing the Olympic Games’ IT network was compromised as early as November 2017.

Olympic Destroyer: a malware that lateralises itself from network to network

Olympic Destroyer is programmed to automatically propagate itself from one network to another by exploiting the supply chain. Specifically, the intrusion set used malware that exfiltrates authenticators, stores them in memory, then replicates and lateralises on other networks by exploiting the identifiers and passwords collected on the previous information system. It then repeats the operation until it reaches its final target.

When activated, Olympic Destroyer deletes the initialisation configuration of compromised machines, preventing them from restarting and then forcing them to shut down. As a result, information systems are severely disrupted.

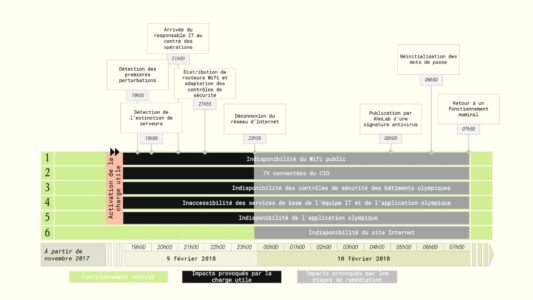

The Olympic Destroyer process and its remediation

Limited impact thanks to well-prepared security teams

Following the release of the malware, the first signs of disruption appeared: temporary unavailability of wifi terminals, access to the application used to print tickets, and the RFID security portals of the Olympic Games.

The IOC’s technical team and its partners quickly undertook remedial work, which involved taking the entire information system offline from midnight to 8am. All connected services, such as the Olympic showcase site, were therefore unavailable for 12 hours.

The ceremony was not seriously affected by the cyber-attack and the restoration phase was quickly completed thanks to back-ups. The teams responsible for IT security had been prepared for this type of incident, in particular through a crisis management exercise to anticipate the unavailability or deterioration of data centres in the event of a cyber attack or natural disaster.

This example serves as a reminder of the importance of carrying out this type of exercise: the expected impact of malware with sabotage capabilities can be limited by the remediation efforts of a prepared and committed IT team. Anticipatory crisis management exercises have proved their effectiveness in mitigating the effects of Olympic Destroyer. For example, the use of back-ups limited the temporary interruption in availability, by facilitating rapid restoration.

A complex false-flag attribution

Attributing a cyber attack is a delicate process. For example, the investigation period to determine the perpetrator of Olympic Destroyer ended in 2020, 2 years after the incident occurred. Attribution requires a match of irrefragable evidence, both technical and contextual, necessitating extremely substantial resources. It also entails a geopolitical risk, since in the event of erroneous attribution, the country behind it could be discredited.

To make the operation more complex, Olympic Destroyer’s code was designed to steer investigators towards false leads, known as ‘false flag’, i.e. a technique whereby the attacker seeks to pass himself off as someone else. False flag attacks make attribution more complex in that they seek to steer investigators towards false leads, particularly by exploiting cognitive biases. For the attackers, the aim is to lead the defenders to ignore or misinterpret artefacts and relevant evidence. In the evidence left behind by the attackers, there is a trade-off between the intentional and the accidental: the false flag ultimately leads to an increase in the cost of the investigation, due in particular to the loss of time.

Computer security researchers first established technical links with malware deployed by alleged North Korean (Lazarus) and Chinese (APT3 and APT10) intrusion sets. US security vendor Cisco Talos has also reported observing similar features in BadRabbit and NotPetya, two sabotage programs that share parts of their code with Olympic Destroyer.

Security firm Kaspersky subsequently attributed the false flag attempt to Sandworm, of presumed Russian origin. According to this source, the attackers’ aim was to disrupt the Olympic Games by targeting the most high-profile event of the Games: the opening ceremony. This information was confirmed by the US Department of Justice, with the indictment of five GRU (Russian military intelligence service) officers in October 2020, following investigations. False-flag attacks are particularly common for these reputedly Russian actors, especially APT28, which has been attributed to GRU unit 26265. This intrusion set has repeatedly used this ruse technique to accredit its public claims for agitation purposes.

What was the background to the cyber attack?

Olympic Destroyer has been deployed in the special context of the Olympic Games, an event where the world’s attention is focused on the sporting competition and the host country.

The Pyeongchang Olympic Games were marked by the sanctions issued by the IOC against Russia. Russia was accused of widespread cheating at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. As a result, in 2018, hand-picked Russian athletes were allowed to compete under a neutral banner, their anthem was not played and the country had to pay a $15 million fine to the IOC. These sanctions did not fail to provoke a reaction from Vladimir Putin, who described them as a ‘humiliation for Russia’ before denouncing a ‘Western plot’ to harm his probable re-election in March 2018.

In addition to the sanctions, Olympic Destroyer is also part of the intensification of Russian cyber attacks since 2015. This is motivated by the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the war of position against Ukraine still underway in 2018. These military events have generated tensions with Western countries, which have economically sanctioned Russia.